Hand flippers. You have to admire Ben Franklin, that quintessential American, for inventing hand flippers for easier swimming. He was eleven years old. It may not be his greatest invention, but it did help get him elected to the International Swimmers Hall of Fame, (not in 1717 when he was eleven, but in 1968.)

Like most Americans, I love the conveniences that have been invented and developed over the years. I’ve never used Franklin’s hand flippers, though I do wear bifocals. And I must say I indulge myself in all sorts of conveniences. If I were to list the conveniences that I enjoy (and ought to be thankful for) the list would include automatic garage door openers, espn.com, Arby’s, direct deposit, refrigeration, Netflix, drive-up windows, disposable diapers (that was a while ago), escalators, frozen pizza, amazon.com, Kensington clickers (for remotely changing power point slides in class), thermostats, self-checkout lines, lawn mowers, Google docs, indoor plumbing, Dunkin’ Donuts, credit cards, remote

car locks, alphabetization, Post-It notes, mail delivered to my home, my computer grading program, car radios, email, the invisible fence for our dog, Turbotax, air conditioning, the private bathroom connected to our bedroom, taco seasoning, interstate ramps, expedia.com, the Land Ordinance of 1785 that arranged Midwestern roads into grids, online fantasy baseball, and, of course, canned chicken broth.

Ah, the pursuit of happiness.

Except that, of course, happiness doesn’t really work this way.

From the above list, Elisa and I made use of the following conveniences when we lived in Kenya: lawn mowers, refrigeration (in our home, but not in Mbote Kamau’s butcher shop where we bought our meat), escalators (going up, but not down, in one mall in Nairobi), indoor plumbing, alphabetization (sometimes).

Nothing else. No canned chicken broth.

And were we less happy in Kenya than we are now in the United States?

No. Imagine that.

If prodded, most American Christians would probably admit that conveniences and material possessions do not produce or guarantee happiness. Our actions, however, indicate we haven’t fully convinced ourselves of this.

For instance, it is common for American evangelicals who have returned from a short term mission trip to Guatemala or Zambia or Haiti to say, “they have so little, and yet they are so happy.”

Interesting, isn’t it? Despite what we tell ourselves, we are still surprised to discover that Christians in poverty could be joyful. And that rich Christians are not always joyful. Dig a little deeper, and we can be slightly amazed to actually encounter joyful Christians who endure hardship, suffering, injustice and deep pain.

A historical observation: there are signs that it is getting harder and harder for American Christians to accept the idea that one can be joyful if we do not have conveniences and material prosperity. A century ago and even fifty years ago, most Christians would not have grounded their own happiness in the center of their theology. Whether we realize it or not, we seem to be doing that very thing today.

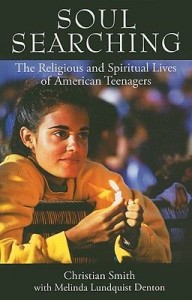

Strong evidence here can be found in Christian Smith’s excellent study of the spiritual lives of teenagers, called Soul Searching. (For a wide range of reasons, I highly recommend  this book). In an extensive sociological study of teens across the country, Smith found that teens may identify themselves as Nazarene or Catholic or Lutheran or Baptist or Jewish, but most of them are really Moral Therapeutic Deists. In other words, if you break down what they really believe, it goes like this: God exists though He is not particularly involved in our lives. We are all basically good. The purpose of life is to be happy. God does actually get active when we are in trouble – then he will come and fix our problems. Smith says in this way of thinking, God is like a Divine Butler.

this book). In an extensive sociological study of teens across the country, Smith found that teens may identify themselves as Nazarene or Catholic or Lutheran or Baptist or Jewish, but most of them are really Moral Therapeutic Deists. In other words, if you break down what they really believe, it goes like this: God exists though He is not particularly involved in our lives. We are all basically good. The purpose of life is to be happy. God does actually get active when we are in trouble – then he will come and fix our problems. Smith says in this way of thinking, God is like a Divine Butler.

Smith is a brilliant scholar, but I’d suggest that we could adjust the Divine Butler metaphor. I don’t know anybody who has a butler. Few people read P.G. Wodehouse anymore (and that is certainly unfortunate). I think instead is fitting to say that most teens see God as a Really Cool App. He’s there in your pocket, and whenever you need him to fix a problem, you pull him out and punch in your request. He’ll just fix it too, because He wants you to be happy. That’s what He is there for. And that is what the Christian church should be doing.

If you read my previous post, you will recall my story about the student who questioned the Christian nature of Malone because I would not let her into a class she wanted. Apparently she thought it was her right to get the course schedule she wanted. It seems that increasingly our culture defines the pursuit of happiness to mean that happiness itself is an inalienable right. And shouldn’t the church support our inalienable rights?

American teens did not invent this thinking. They are just being socialized by the culture they grow up in, which is why most believe the purpose of life is to be happy.

This is Bad Theology for a number of reasons. It assumes that the world and even God Himself revolves around us as individuals. It fails to adequately account for our individual sinfulness, for if we constantly try to arrange everything according to our individual desires for happiness, we will make others around us more miserable. Since we are in control of the Really Cool App, we place God on our terms, turning to him only when we are desperate. And then, upon discovering that the world is not ordered for our convenience, that we can’t always get what we want, and that we can’t really control the Really Cool App, we will get very frustrated and disappointed with God.

I don’t know how these impulses will unfold in American culture or the American church in the years to come. I do know from personal experience that at the desperate point where the world does not work the way I want, I finally am able (after I get over my frustration and disappointment) to accept the grace of God in a way that I had not before. Joy follows.

That is my hope for the future of American Christianity.