I was a computer science major my first year in college. My students think this is hilarious, because of what happens when I use computers in class. My power point crashes, regularly. A file I saved to a drive mysteriously disappears. The sound doesn’t come through on a video clip and I frantically check six different volume controls in the system to try to recover it. They might think this is all incompetence on my part. I tell them that there is an e-conspiracy against me by advanced technology.

Whatever the source of my current conflicts with computer systems, it is certainly true that I didn’t really have good judgment when I thought computer science would be my thing. I could do the work, but I wasn’t very good at it. Nor did I get much satisfaction or joy from it. As it turned out, history was a much better major for me.

I didn’t see myself very clearly. But why is that? Of all the things we try to understand in this world, we ought to understand ourselves better than anything. Right?

Well, no.

My problems in seeing myself clearly are connected to themes I have been blogging about lately. That’s why I told my embarrassing grad school story. And why I argued that we have blind spots about race, we have blind spots about religion, we think we are better at being wise than other people, and we have difficulty in thinking clearly about Islam and politics and football.

Why? Sin affects our thinking.

We often don’t think about how sin affects our thinking because….well, sin affects out thinking. In our pride, we don’t want to admit that we are wrong. We don’t want to admit that we might be misguided in our convictions for what ails the health care system, our boss, the Cleveland Browns, or the stupid traffic light system up on Maple Street here in North Canton, Ohio. (Don’t get me started). We cherish our sense that we have it figured out.

That’s where I blame Adam (the one who hung out with Eve).

But American culture exacerbates this problem by encouraging us to believe that we really do see clearly.

Take, for instance, certain developments in psychology in the 1950s. Carl Rogers, perhaps the most popular and influential psychologist of the era, promoted what he called “client-centered therapy.” Rogers held great optimism in the ability of humans to make choices that were good, true and in the terminology of the time, “self-actualizing.” In other words, trust yourself.

Boy, what great news that is! Of course I am correct about the health care system, the Cleveland Browns, my boss, and the stupid traffic light system up on Maple Street. And while I’m at it, let me tell you what’s wrong with Islam, racist policemen, the Democratic party, Fox News, NPR and AT & T. I can see it all, clearly.

And then I’ll blog about it. (Why is the joke so often on me, anyway?)

This therapeutic turn towards trusting our “self” gained authority in the 1950s and 60s because Rogers and others like him argued this methodology was scientific. As he explained, his client-centered therapy stemmed from a discipline with a “genius for operational definitions, for objective measurement, its insistence upon scientific method, and the necessity of submitting all hypotheses to a process of objective verification or disproof.” How can you argue against that? Rogers’ psychological analysis for why we should trust ourselves carried the authority of science.

That’s where the scientists (and those who thought they were scientists) come in. Most intellectuals of the 1950s (including those professors who taught everyone in college) held a faith that scientific methodology would help us all see clearly. Science had enabled humans to produce jet airplanes, television and the polio vaccine, had it not? Scientific advances in the realm of psychology should produce “self-actualized” persons as well, should it not?

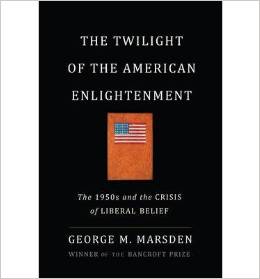

In some ways, this was not new. Faith in this version of scientific thinking had been since the Enlightenment. And faith in the individuals who trusted themselves had been around since the nineteenth-century Transcendentalists. But as George Marsden points out in The Twilight of the American Enlightenment, this doesn’t mean the two are actually compatible. After all, scientific methodology is designed to determine truth by the study of objective realities while faith in the self looks inward, subjectively, for truth.

(By the way, Marsden’s book, which is geared for non-academics, is a very accessible, clear, and compelling read if you want to learn more about the development of intellectual ideas in America in the 1950s and how it led to the culture war of the 1980s. You don’t have to be a professor or a pointy-headed intellectual to understand or enjoy it).

(By the way, Marsden’s book, which is geared for non-academics, is a very accessible, clear, and compelling read if you want to learn more about the development of intellectual ideas in America in the 1950s and how it led to the culture war of the 1980s. You don’t have to be a professor or a pointy-headed intellectual to understand or enjoy it).

As Marsden also points out, there is one more significant difference between thinkers of the 1950s and those of the Enlightenment: Enlightenment thinkers believed in a Creator who established moral laws, while psychologists and scientists alike in the 1950s believed that moral laws were produced by humans as they evolved over time.

In other words, psychologists and scientists alike by the 1950s believed humans created morality. By implication, they placed a great deal of faith in the ability of humans to see clearly, apart from any reference or guidance from God. God was irrelevant because He may or may not exist, anyway. Instead, the scientific examination of the outward objective world and the psychological examination of the inward subjective world would help us see more clearly. This was communicated to Americans through universities, popular magazines, TV shows and movies.

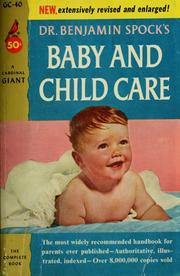

The best selling expert on child care, Dr. Benjamin Spock, made this point explicitly in his opening line to parents in The Common Sense Book of Baby and Child Care: “Trust yourself.” He told parents that “your baby is born to be a reasonable, friendly human being.” The Baby Boomer generation grew up with this message.

And if we can trust ourselves, and if our babies are going to naturally be reasonable, and if we have this on the authority of scientists and psychologists, then we all must really think clearly, don’t we?

Of course, the idea of sin is long gone by this time. Let alone the idea that sin affects our thinking.

And that makes it even harder to see, let alone admit, that our thinking may be distorted.