Episcopalians are generally a pretty respectable lot. Well-educated. Self-disciplined. Reasonable. Dignified. Prudent. There is often a certain gravitas to them.

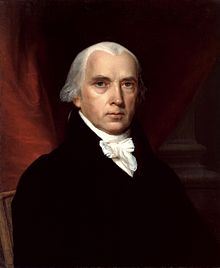

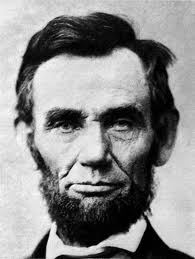

Consider, for instance, the following list of Episcopalians: George Washington, James Madison, T.S. Eliot, Eleanor Roosevelt, Buzz Aldrin, Sandra Day O’Conner, Colin Powell, Batman.

Not a single one of them would embarrass you at a dinner party. If you needed somebody to lend dignity to a national event by saying a few words at the opening ceremony, any in this group would make you proud. Install any one of them as president of a university, and the U.S. News and World Report rankings of the institution would automatically jump up ten places, even if it was already ranked at number five.

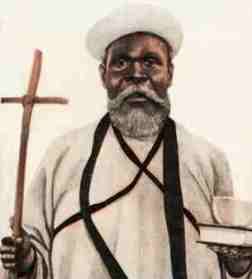

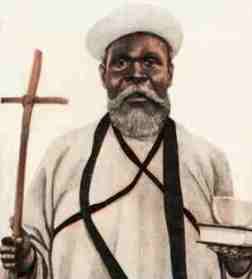

And then there is William Wadé Harris.

Sure, this African Christian started down the path of respectable Episcopalianism. In Liberia in the 1890s, Harris served as a catechist and teacher for the Episcopalian mission near Cape Palmas. Working for the missionary machinery that brought education, Christianity, bureaucratic government, scientific farming and modest clothing styles to Africa, Harris was an unimpeachable product of, in the terminology of the day, “the civilizing mission.”

At least that is what it could look like for a while, from the outside. It became harder to see Harris as a respectable Episcopalian, or any kind of Episcopalian, for that matter, in 1910.

Harris was in jail that year. He had been convicted of treason after raising the British Union Jack on the beach and yelling at the Americo-Liberians (black immigrants from the United States who dominated Liberia) to get out of his country. But there is more. While in jail, as Harris explained later, the angel Gabriel visited him in a trance. The angel descended three times and felt like ice on his head. According to Harris, Gabriel anointed him as a prophet like Elijah, Daniel, Ezekiel and John, and instructed him to burn fetishes and preach Christ, who was about to usher in the peace of a thousand years, as spoken of in the book of Revelation.

I’m pretty sure that this sort of thing never happened to George Washington.

And I can’t see Eleanor Roosevelt casting out evil spirits, miraculously healing the sick, adopting polygamy, or cursing dockworkers who worked on Sunday. All these actions were attributed to Harris, though. He sometimes engaged African medicine men in showdowns of supernatural power. Some say he raised the dead to life.

So one does not know what would happen at dinner parties if Harris were invited.

Catholic and Methodist missionaries, who were almost as respectable as Episcopalians, did not know quite what to make of him, either. His evangelistic tours through West Africa after 1910 brought hundreds of thousands of Africans to the faith, new Christians who followed his instructions to build churches and wait for white missionaries to arrive with Bibles. The missionaries, of course, were pleased to see their churches overflow with converts. But they were not sure if Harris’ baptisms were conducted properly. They did not approve of polygamy.

This, of course, raised intellectual and theological challenges to the missionaries of his day. But Harris also raises challenges to westerners today. Some secular anthropologists like Lionel Tiger often assume that a certain kind of functional coherence exists in traditional religions. They assume people of other cultures are content with their religious faith and values. Yet traditional African religions, like religions in the West, are not as tidy as assumed. Nor are their adherents necessarily content with them. Many west Africans felt conflicted about the power for good and evil that they experienced in their traditional religions. William Wadé Harris proclaimed that his African audiences could encounter a spiritual power – the power of Christ – that would release them from the power of their fetishes. Hundreds of thousands jumped at this chance.

There is a challenge here to American evangelicals, as well. It is easy, as an American Christian, to view African Christians as if they are American evangelicals with livelier music. Harris, however, just might make some American Christians uncomfortable if he were to speak in their Sunday School. Just what are we to do with polygamy and evil spirits, anyway?

We need to keep this in mind: Christianity that has been transmitted to African soil often bears fruit that may look and taste different from what you’ve plopped on your plate at the Sunday potluck. Variations of world Christianity can raise issues that many American evangelicals have not considered. That is just one reason why western Christians don’t have all the answer to issues facing Africa. As far as I know, the seminaries where we send our ministers don’t offer courses on African fetishes.

Nor do African Christians have all the answers, either. The challenge, then, is to utilize our resources to collaborate and learn from one another. The process will probably raise uncomfortable questions, but that happens in the Christian faith. It can even happen to Episcopalians.