If you are like me, you know that in ordinary, daily life, it is very difficult to offer constructive criticism in a civil and respectful manner. And it is darn near impossible in two areas of American public life: political elections and anonymous comment sections on the internet.

Granted, there are people, some of them are even creatures called politicians, who are able to disagree in a thoughtful, civil and constructive manner. But it is very hard, partly because many voters do not pay attention to this kind of discourse. The temptation to revel in the mudslinging thrown by “our people” is far too alluring to many of us.

On the other hand, political mud-slinging is not just distasteful to many Americans, it tempts many to avoid political engagement as much as possible. That is another unfortunate consequence.

So, wouldn’t it be great if we could go back to that time when elections weren’t characterize by insults, intentionally misleading characterizations and outright lies about the opposing candidate?

And that time would be…..when?

How about the 1800 election? In my last post I gave props to John Adams and Thomas Jefferson for how they handled the election. Good, healthy losing. Good, healthy winning.

But there was more to that election. As the first presidential election in which clear factions had formed in competition for the top position, some rather outrageous things were said by politicians and media leaders. Ordinary people believed a lot of these outrageous things.

For your entertainment and increased understanding of the world, I have a video that catches some of the spirit of the rhetoric from the 1800 election:

Several notes:

1. For the historically gullible among you: neither the internet nor television actually existed in 1800.

2. The quotes here are edited and taken out of context, but they do reflect the flavor of what was said and some actual phrases that were used.

3. The 1800 election, like all elections, also produced people who gave thoughtful, respectful and constructive criticism.

4. Jefferson and Adams did not actually say these things publicly because candidates did not actually campaign publicly then — they let their supporters campaign for them. (Hey, wouldn’t that be great?) The mudslinging comments in 1800 were from their supporters. (OK, second thoughts: maybe we don’t want to put all the political rhetoric in the hands of party supporters.)

My point is that name-calling, false accusations and outright lies have been present since the beginning. This is not new.

So does mud-slinging matter?

Well, it is protected speech under the Constitution, and rightfully so. This kind of rhetoric is, on some level, unavoidable, since “men are not angels” as Madison said, (or “all have sinned and fallen short of the glory of God” as Paul said.)

However, that does not mean it is healthy for our society. It would be better if candidates (and their supporters) could manage to be above all of that. But it is really hard to pull off effectively. So we have to live with some level unhealthy rhetoric in our society.

Still, not all uncivil language is created equal.

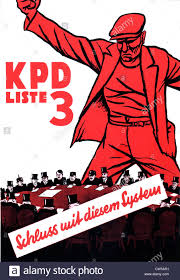

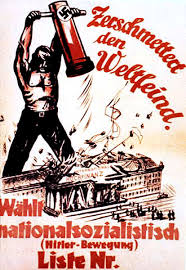

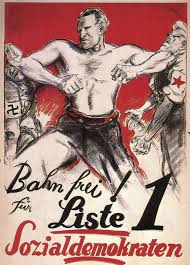

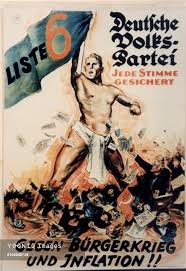

For instance, consider the following campaign posters from Germany between 1929 and 1933. At that time, Germany was a democracy (known as the Weimar Republic), but it was a fragile democracy.

These campaign posters reveal problems within the political culture of Germany at that time. Take a good look at the images.

Communist Party, Liste 3:

“An End to this System”

Nazi Party:

“Smash the World Foe, International High Finance”

Social Democrat Party, Liste 1:

“Clear the Way for List 1”

The People’s Party, Liste 6:

“Against Civil War and Inflation!!”

What underlies these forms of political rhetoric?

They are signs that Germany at that time lacked a tradition of a loyal opposition.

To review: healthy democracies assume that disagreement is legitimate, dissent is a healthy part of society, and political opponents should not be treated as if they are enemies to the nation.

Also this: citizens recognize that their loyalty to the system of democracy is greater than their loyalty to a particular party or politician.

The lack of a loyal opposition in the Weimar Republic was significant because, as you may know, Hitler was able to take over the whole system in 1933. That story is often told as if Hitler were some sort of “genius” who was able to dupe a bunch of gullible Germans. But that analysis misses some critical points about the political culture of the Weimar Republic.

Hitler was a skilled orator and political manipulator, but he was no genius. He was able to succeed because he took advantage of a number of serious political ailments in the Weimar Republic, ailments that many non-Nazi politicians and political parties also contributed to.

In other words, it would be helpful to consider what sort of ingredients went into the recipe of the Weimar Republic. What made it possible for a large number of people to accept the Nazis and the communists as legitimate political options? There were many, but let me list a few on the political discourse side of things.

(Shameless plug for the importance of good historians: If you want to read a fascinating, historically-solid account of how Germany ended up in the hands of the Nazis, I recommend that you read The Coming of the Third Reich by Richard J. Evans.)

First of all, several political parties in the Weimar Republic intensified a sense that force and violence were valid measures to turn to, under the right circumstances. Parties actually had their own private para-military units which would intimidate, beat up, shoot and sometimes kill political opponents and supporters. For the Nazis, these were the Brown Shirts. Other parties had their own uniformed gangs. Can you imagine Republicans and Democrats with their own uniformed military force, dressed in red and blue shirts, roaming the streets outside of polling places?

But here is my key point: some forms of rhetoric, images and discussion encouraged many German citizens to accept violence in politics as legitimate. Take another look at those campaign posters. Several political parties, particularly the Nazis and the Communists on the extreme right and left, (who together captured 52% of the vote in 1932) did not treat other parties as if they were legitimate. Even the less extreme parties, like the Social Democrats and People’s Party, were pulled into this kind of campaigning. Politicians commonly accused opponents as “enemies of the Reich.”

And once you have labeled political opponents as enemies of the nation, it is easier to attach the “enemies” tag to all sort of people. German Jews, of course, were the most notable victims of this process.

Of course, Hitler was not loyal to the system of democracy. Neither were the communists. Hitler exalted himself and his party above the system. He equated his ideology with the nation of Germany.

There were many other factors that went into the rise of the Nazis. But political rhetoric was a key part of the process.

Americans (and other stable democracies) can be thankful for a tradition of loyal opposition. American politicians rarely refer to their opponents as “enemies” of the nation. They do not argue that violence is a legitimate tool to use against their opponents. That’s the part we do well, without realizing it.

But we need to tend the garden. What we say and how we say it matters. There are ways that our rhetoric and discourse can start to slip in unhealthy directions. Some politicians treat criticism as if it is not just incorrect but illegitimate. Some people revert to rhetoric that characterizes political opponents as enemies of the nation. And some people (fortunately they are usually non-politicians without much influence) will speak of violence as if it were an acceptable response to political opponents.

Our challenge? Rhetoric is a very slippery and difficult substance to assess. What kinds of rhetoric are constructive forms of dissent and what kinds of rhetoric pull us into unhealthy spaces? The extremes are easier to identify than the fuzzy places in the middle.

So, let us think carefully, and humbly about what we are saying and how we are saying it.