With “Lincoln” in the running for best film at the Oscars this weekend, I feel like I’m a grumpy, kill-joy, nit-picking, griping curmudgeon of an historian. After all, I am devoting not one but two entire posts to my complaints about the film.

So let me repeat an earlier point: it’s a great film. Go see it. See it twice. I’m serious.

Then, read some good histories of the Civil War. This will give you a more complete picture and a deeper understanding than Spielberg leaves you with.

This is where my grumpy, kill-joy, nit-picking, griping, curmudgeonliness is coming from: Spielberg’s film, by itself, gives us a misreading of how abolition came about. It misses the critical part of the story.

Consider this question: who is the real hero of abolition in the United States? Is it Abraham Lincoln? Hmm.

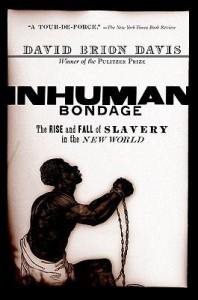

Let us return to 1860. In that year there were almost 22 million people living in the northern states that would soon make up the Union. How many of those northerners were abolitionists? The numbers are hard to determine with precision, but about 2% of the population belonged to or supported abolitionist societies. It’s important to understand that one could be antislavery but not an abolitionist. Many northerners did not like slavery, did not want it to spread to the West, and/or thought it was morally wrong. Many of these same northerners, however, worried that setting free 3 million blacks would create huge

social, economic and political problems for the nation. They did not want to mess with the system. So abolition was a very unpopular movement, even in the north. That’s why William Lloyd Garrison was nearly lynched by a mob in Boston. That, and the fact that he was obnoxious.

Abolitionists were trouble-makers. And Lincoln was not among them. Although he was actually well ahead of many white Americans in his views on race, equality and antislavery, he still had some issues to work out in 1860, as I explained in my previous post.

Now jump ahead to 1865. Lincoln was firmly, sincerely and rather masterfully pushing through the 13th Amendment. He was supported by almost all the important Republican politicians, many soldiers in the Union army, and a great deal of the American public. Lincoln, and many white northerners had turned into abolitionists in less than five years.

It was a remarkable transformation.

How did Lincoln, and many northern whites like him, come around to this position? Now this is a movie I’d like Spielberg to make, though I’m not sure what he would call it. “Lincoln: the Prequel?” “The Good, the Bad and the Ugly Lincoln?” “Lincoln and the Phantom Abolitionist Menace?”

Here’s the point: Abraham Lincoln was led down this path by the unexpected and complicated events of the Civil War. So, if you are looking for heroes who pushed Lincoln on the abolition issue, you can turn to African Americans. And abolitionists.

Consider the role of blacks and Union policy in 1861. At that time the Union was not fighting to eliminate slavery. When slaves ran away and made their way into Union army camps, Union officers were instructed to return them to southern masters. Free blacks who volunteered to fight were turned away and were not allowed in the Union army. These were all official policies established, approved and enforced by Abraham Lincoln and his administration.

Blacks began violating those policies. Newly freed blacks in South Carolina and Louisiana formed regiments on their own, anyway. A black man, Robert Smalls, took it upon himself to steal a Confederate ship in the Charleston harbor and sail it out to the Union blockade. A group of blacks in Kansas formed a regiment on their own and actually joined a skirmish against Confederates.

More importantly, slaves, who were considered property by both southerners and War Department policies, refused to behave like property and sit still. They kept running away to Union camps when the armies got close enough. In the summer of 1861, General Benjamin Butler saw the military logic of holding on to this property that kept landing in his lap. If slaves were property, as the logic goes, and the rules of warfare allowed an army to keep property of the enemy as contraband when it fell into their hands (think guns, wagons, ammunition, horses, etc.), then slaves could be declared contraband when they made their way into the hands of the Union army. The War Department eventually saw the military logic of this position, changed its policies, and declared that slaves who had worked for the Confederate army would be declared “contraband.” But the Union would not accept other slaves working for private landowners, the War Department (and Lincoln) declared, because it was not, after all, trying to eliminate slavery in the southern states.

As the fighting of 1861 continued on into 1862, the Union kept on losing key battles. This helped the cause of abolition. I love the irony here. Every Union loss and every Confederate victory brought the nation closer to eliminating slavery.

How? Black and white abolitionists kept making arguments that the Union could defeat the Confederacy by abolishing slavery. Slaves made up 40% of the Confederate population, they argued, and provided the labor for most of the Conferedate economy. Slaves made up one third of the workforce of the primary Confederate producer of armaments, the Tredegar Iron Works in Richmond. More than half of the miners in southern iron, lead, and salt mines were slaves. Why not encourage the elimination of slavery, since most northerners already thought it was wrong, and help the war effort at the same time? As Frederick Douglass declared, “To fight against slaveholders without fighting against slavery, is but a half-hearted business.”

And so Lincoln brought forth the Emancipation Proclamation in late 1862.

The abolitionists were right. Emancipation greatly aided the Union war effort. Consider this: over the course of the war, 500,000 slaves ran away, the vast majority after the Union had changed its policies. That’s 1 out of every 8 slaves. Not only did this weaken the workforce for the Confederate military and economy, but 200,000 of those freedpeople joined the Union military system as unlisted laborers.

And then there were the black soldiers. Lincoln and the War Department were reluctant to put guns in the hands of blacks, but blacks persisted in their desire to fight. In early 1863, abolitionists pressured the governor of Massachusetts, John Andrews Albion, to form black regiments. The governor, in turn, pressured Lincoln to allow him to present the Union army with two regiments of blacks. Lincoln finally agreed. There were more political battles over equal pay and allowing blacks to fight (the film “Glory” captures this well). But in the end, 185,000 blacks fought for the Union army, the vast majority of whom were slaves who had run away. Consider this number in light of the fact that Robert E. Lee typically had about 50,000 to 70,000 soldiers under his command when he fought in Virginia.

By 1864, most Union soldiers had come to realize that abolishing slavery would help them win the war. A great book detailing why soldiers fought in the Civil War, For Cause and Comrade, by James McPherson, demonstrates this effectively. Lincoln had become firmly converted to the cause of abolition by 1864, as were many Republicans. So the time was ripe, in early 1865, to pass the 13th Amendment.

converted to the cause of abolition by 1864, as were many Republicans. So the time was ripe, in early 1865, to pass the 13th Amendment.

This, then, is how the paradigm shift occurred: a few whites first became convinced that abolition was necessary, just by the sheer morality of the issue. But most whites first became convinced that abolition was necessary because it would help them win the war.

This is how human nature works. It is hard to see and do what is right when it costs us something. It is easier to see and do what is right when everyone else (and the cultural norms) uphold what is right. It is easiest to see and do what is right when we also get some benefit in return.

My biggest complaint with Spielberg’s Lincoln is that it gives the impression that one great, pure man brought about “the greatest measure of the nineteenth century.” The reality is that while most of the country followed Lincoln’s lead, Lincoln was following the lead of runaway slaves, free blacks and abolitionists. And none of this would have come about but for the unpredictable and unanticipated events of the Civil War.

Let me be so arrogant as to suggest that Lincoln probably understood this. Though rather unorthodox in his Christian beliefs, he did believe very deeply in providence. He also believed that the ways of God were mysterious and hard to discern. Lincoln did not believe that any individual or collection of individuals could overrule providence and by sheer will or masterful politics, compel events to conform to one’s expectations. I give Lincoln credit for that. (An aside: for a great discussion of Lincoln’s role in the theological debates over the Civil War, click here).

I also give Lincoln credit on another score. Many people today think we are fully baked and incapable of transformation. That’s probably true if we are unwilling to change. But Lincoln was willing to change his views of abolition and racial equality. It came first through his primary desire to save the Union and defeat the Confederacy. But he was changing in the end, which is more than can be said for many others. That, it seems to me, is a more admirable quality than political astuteness.

It was a transformation that came about because of the actions of hundreds of thousands of African Americans whose names we will never know.