And now, for a holiday that Americans don’t spend any money on….because it is British.

Many years ago, when I was teaching at Rift Valley Academy in Kenya, I took part in an old English tradition on Boxing Day. As I found out, Boxing Day has nothing to do with that dubious athletic goal of punching another person senseless, (sorry for sounding like an elitist snob here, but why do we consider boxing to be a “sport?”) Boxing Day, rather, stemmed from a 19th century tradition when people would box up food and other items on December 26 to take out to the neighborhood poor.

As a former British colony, Kenyans still celebrated Boxing Day. Like the British, though, few Kenyans actually boxed up food for the local poor any more. In fact, most Kenyans, like Americans, may not even know what this holiday was all about. The Brits themselves may be a bit fuzzy themselves. From what I can tell from my English friend and colleague, Malcolm Gold, when he was growing up the English primarily celebrated Boxing Day by watching “The Wizard of Oz” on the telly. Because, you know, munchkins and flying monkeys.

At any rate, one year when I was in Kenya, the chaplain of our school for missionary kids had decided that it would be good to resurrect the old English custom since there were a lot of poor in our area. He had collected money from the students during the previous term and then purchased goods to take out to the community on Boxing Day. I went along to help because it sounded like a good thing to do. And I didn’t have TV reception to get “The Wizard of Oz.”

Our chaplain had worked with the Kikuyu elders of the local church to identify about a dozen of the poorest households in the community. In Kenya this means those who are what economists would call “desperately poor” rather than just “poor.” These people had far fewer resources than those in poverty in the US — we’re talking about people who make something like $200 to $600 a year, with no soup kitchens, welfare or rescue missions around. They were, of course, quite grateful to be getting a box full of food. These people knew what it was like to have days when you did not have much, if anything, to eat. And that is why I was rather surprised to see that a number of them got even more excited (as did a few neighbors who had gathered around) to find that our chaplain had included a Kikuyu Bible in the box.

Think of this: you are poor, you sometimes don’t have enough food to eat, you receive a box of food, but you get most excited about a Bible in the box?

I could end the post right here with a nice evangelical moral about how valuable the Bible is. I won’t do that though, for two reasons. First of all, it is a little too simple. It sounds a little too much like the sappy moralistic stories that Victorian Christians used to tell their children in Sunday School to get them to be good. Therefore it would come off sounding shallower than what it really was. (I ought to point out, though, that those same sappy Victorian Christians did think they ought to personally get up and try to do something to help others, which is much more commendable than sitting at home watching Judy Garland and Toto cavort with a scarecrow. Though, you know, that would be fun).

Today you can get the Kikuyu Bible online for free…if you have enough economic resources to have internet access.

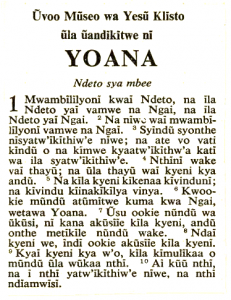

The second and primary reason I don’t end the story here is because there are important theological and cultural dynamics at play here. These were Bibles that had been translated into Kikuyu. At that time, for reasons that I don’t understand, there had been publishing problems in Kenya. Kikuyu Bibles were in short supply. But not other Bibles. There were plenty of English and Swahili Bibles to be found. Most of the Africans in our community spoke Kikuyu, English and Swahili. So, if they could get Bibles that they could read, what was so special about a Bible in Kikuyu?

The answer lies in understanding how language works and what that has to do with the Christian faith. A friend of mine who is an anthropologist and a missionary talks about the importance of the “heart language.” For those of us who grew up in the United States and really only know one language, this is kind of hard to grasp. But for those who know several languages, there is often something special about the “mother tongue” or language that one learned first, as a child. Great truths take on far more power, meaning and significance when they are communicated in the first language one learned. It might be something like the mix of passions and emotions that can arise within you when you hear a favorite old hymn or song. For those who grew up speaking Kikuyu before learning Swahili or English, a Kikuyu Bible will have far more meaning and power.

The “heart language.” There is a lot to this — important theological, cultural and historical implications to this relationship between language and culture. And it is important for the church today. My plan is to explore these in the next couple of posts.