No, this is not a post setting up a heavy-weight battle between two powerhouses who slug it out, like the Rome vs. Carthage, or the Yankees vs. the Red Sox, or Wile E. Coyote vs. the Road Runner.

Not exactly, I guess. But you know where my faith commitments lie. So I confess that I want to make a theological point about how God works in the world and what that has to do with language.

If you have had some instruction in world religions or if you just pick things up about the world, you might know that, when it comes to language, Christians and Muslims view their sacred texts in different ways. Christians believe that the Bible can be translated into any language and it will still be sacred. It’s still the Bible. Muslims, however, believe the Qur’an is only the Qur’an if it is read in Arabic. You could translate it into English, but if you do that, it is no longer sacred and it is no longer authoritative. In other words, to truly read the Qur’an as a sacred text, one has to read it in Arabic.

So what?

I began to understand the significance of this a number of years ago when I participated in a seminar led by Lamin Sanneh. Sanneh, who today is Professor of World Christianity at Yale Divinity School, grew up as a Muslim in the Gambia. His people were the Mandinka. As a young boy, Sanneh was sent off to Qur’an school to learn the sacred scriptures. That meant, of course, that Sanneh had to learn Arabic. As I recall him telling the story, Sanneh internalized the message that his own language, Mandinka, which was spoken at home, in the market, and in the fields, was not a language fit for the holy things of Allah.

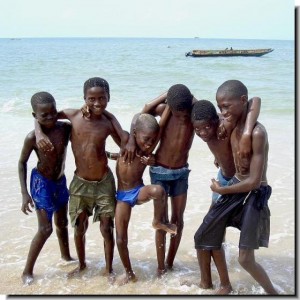

Years later, Sanneh was drawn to Christianity. In the midst of the process of exploring Christianity, he had been struck by the reality that the Bible was translated into the Mandinka language. All his Islamic training, of course, had taught him that one had to work very hard to master a very special language in order to approach Allah, (assuming one was a privileged male with access to Qur’an school to begin with.) Yet here was Christianity, translating its sacred text into Mandinka. What kind of God was this, whose holy words could be spoken in this language used by little girls, and pottery merchants, and goat-herders?

Translation, then, not only made it possible for the Bible to be spoken in Sanneh’s heart-language. Biblical translation implicitly declares that God cares about the Mandinka language, Mandinka culture, and Mandinka girls and Mandinka pottery merchants and Mandinka goat-herders. Not to mention Swedes, Brazilians, Kikuyu, Japanese, and Arabs. This is a profound and mysterious way the incarnation works. God meets us where we are.

I was reminded of this while reading John 4 this morning. This is the wonderful story where Jesus stops to talk to the woman at the well. The setting alone blows me away, when I think about it. God did not have to become flesh. And even then, God could have appeared anywhere in history, in any way, to anybody. So, of all the prominent, godly, smart, talented, or notable people down through history whom God could speak to, God chooses to have a compassionate face-to face conversation with an unknown Samaritan woman of dubious reputation.

What kind of God is this?