James Bond, missionaries, and world Christianity?

You may be thinking that I have a topic that really does not fit in my contest about which individual we should be more interested in. You may be thinking that because I have written a book about missionaries and world Christianity, I am looking for a cheap way to turn the topic back to my interests. You may be thinking that I am playing a literary bait and switch here, using James Bond to hook your interest in something totally different.

You may be right.

But then, again, you may not be.

Granted, the nature of James Bond films compels me to shift the point a bit. I can’t have a sensible contest based on the question of how world Christianity plays out in these thoroughly secular films. There is, however, a closely related topic to world Christianity. What happens when the Bond films cross cultural boundaries? What does cross-cultural engagement look like?

Let’s just say, not great. Bond films exude an aura of British superiority. This ethnocentrism, apparently, was even stronger in the Ian Fleming books. In fact, the whiff of British exceptionalism was so strong that some storylines had to be revised when the books were made into movies for American audiences. I guess American audiences don’t like to be depicted as inferior. Who knew?

It gets worse, however, when dealing with non-Anglos, particularly in the books and early films. The villains are often nonwhites and they are often deformed. Furthermore, nonwhites just don’t have the brains, the sensibility, the skills, or the enlightened rationality of the Brits (or the Americans, for the film versions). In “Dr. No,” Bond enlists the help of a Jamaican assistant to investigate Dr. No’s hideout, but this black guy, like the other

Jamaicans, is deathly afraid of the rumors he has heard about a dragon that inhabits the island. The “dragon” turns out to be a flame-throwing tractor with big teeth painted on the front. The foolish, superstitious and cowardly Jamaican assistant gets killed in the ensuing battle, but the film viewers are not supposed to care because, like the villains, his life doesn’t seem to matter much. (It should be noted that even though they are evil, none of Dr. No’s scientific assistants are black. His hideout displays a level of intelligence that blacks do not seem capable of achieving.)

The Jamaican assistant’s fear of the “dragon” emerges from a common depiction of race and religion that comes straight from the 18thcentury Enlightenment thinker (and Brit) David Hume. According to Hume, less rational people, particularly those who have not been blessed with civilization, believe in irrational religious beliefs that express themselves in superstitious behaviors. Enlightened and rational people, on the other hand, build sophisticated, morally superior civilizations that progress beyond the ignorance of previous

ages. “I am apt to suspect the Negroes, and in general all other species of men, to be naturally inferior to the whites,” Hume wrote in Essays, Moral and Political. “No ingenious manufactures among them, no arts, no sciences.” Most people easily spot the racism in Hume’s thinking. However, his claims about religious faith, which masquerade as rational truth, still infect much of the western world today

Samuel Sharpe, who lived half a century after Hume’s death and more than a century before the first James Bond film, would seem to qualify as a superstitious and naturally inferior “species of men.”

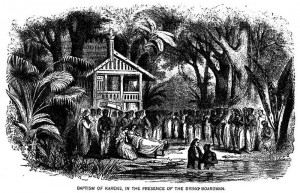

But here is where world Christianity helps expose fallacies in Hume’s and Fleming’s brand of Enlightenment thinking. Sharpe’s relationship with the missionaries brings out point. The leaders of this 1831 Jamaican rebellion (as well as a similar rebellion eight years earlier in Demerara, on the north coast of South America) were deacons and evangelists. Baptist, Methodist and Presbyterian missionaries from Britain had been ministering among the slaves for the previous decades. Slaveowners, in fact, complained bitterly that the missionaries were spreading radical and subversive ideas about equality and abolition among the slaves. (Hume, who believed that evangelical religion led to social disorder, political radicalism, emotional derangement and psychological delusion, would have agreed).

The missionaries, however, did not promote, plan or lead the rebellion. In fact, they warned the slaves not to plan any resistance, they downplayed the possibility of emancipation getting passed in Parliament, and they did not even know of Sharpe’s rebellion until right before it occurred.

In other words, this movement took off without missionary leadership, in ways they did not expect and could not control. That is usually what has happened when a movement of Christianity emerged and grew after it had crossed cultural boundaries.

There is also a theological point here about cultural blind spots. Although they were generally favorable to antislavery ideas, British missionaries preached a simple evangelistic message and stayed away from topics of abolition. The slaves who had converted to Christianity, however, saw implications in the gospel that white Christians were slow to recognize: the Exodus story indicates that slavery is not God’s plan for the world. The same held true for Christian slaves in the American South. On Sunday mornings they might hear a white minister preach on the text, “slaves obey your masters,” but on Sunday nights, in the privacy of their separate worship, they heard slave preachers draw conclusions about freedom from the Gospel. And they wrote and sang scores of spirituals with themes of being released from bondage in Egypt and entering in the Promised Land.

These slave spirituals could get emotional, a point that Hume would have looked on with distaste. The slaves could not boast of “ingenious manufactures” or cool Bondian technology. They did not display the marks of a “civilized” people. But they understood truths unknown by rational philosophers like Hume and clever writers like Fleming.

That’s interesting.

Score:

James Bond 2

Samuel Sharpe 3