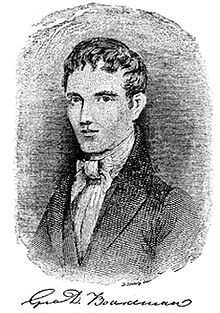

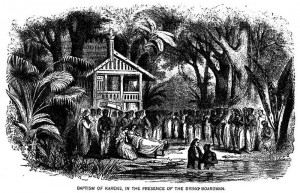

George Boardman dying while watching Karen Christians getting baptized. That makes him an evangelical hero doesn’t it? Or does it?

And now it is time to address the question I posed in my previous post. Was George Boardman a jerk?

Not any more than I am.

Of course, that doesn’t really answer the question, because I just might be a pretty big jerk myself. Or I might not be. Or I might be a jerk sometimes but not at other times. You can ask my wife and kids about that, but I’d prefer you not.

The reality is that missionaries, including “Boardman of Burma” were actually a lot like the rest of us. They may have been faithful Christians and deeply dedicated to their ministry, but they also had their flaws and blindspots. They should not be divided into simplistic categories of heroes and jerks.

Why didn’t Boardman respond immediately to the Karen inquirers? The real answer requires a more complicated consideration of his personality and the cultural situation he was in. This kind of explanation, quite frankly, doesn’t fit well into the limited space of the typical blog. If I could accurately categorize him as either a jerk or a hero, I’d be able to explain it all right here. But I can’t. He and his situation were more complex than that. So you’ll have to read my book for a more complete exploration of those issues.

And since you may not like that answer, I’ll give you a shorter one: Boardman could not predict the future. He had invested himself in the Buddhist Burman people in the city, not this uncivilized nomadic group of Karen people in the jungle. It was a big step for him to let go of his plans. To do so would mean he would have to stop trying to control things according to terms he had laid out for his ministry. He would have to go off to the jungle to operate by the terms of Karen culture. That would not be easy for any of us to do.

Or how about this: an even shorter answer, and one that is probably better because it has depths of meaning to it, comes from Randall Forbes’ great comment on my previous post. Boardman sounds like Jonah. Ponder what that means. There are a lot of layers to that short book of the Bible.

Now, if you are an evangelical Christian, you are probably drawing a spiritual lesson from this story. And if you are an American, you are individualistic, which means you are applying the lesson to your own personal situation. You probably recognize that there have been times in your life when you had plans laid out a certain way and God came along and presented something different to you, which was difficult in the short run, but much better in the long run. Great. I’m glad you drew that lesson without me even having to point it out to you. Well done.

But if you are an evangelical Christian and an American and individualistic, it is also quite possible that you did not naturally respond to a story like this by thinking about the larger social structures and cultural influences that influence our thinking. So here, free of charge, is a larger point that deals with social structures and cultural influences that influence our thinking: the very question that I posed, “Was Boardman a hero or a jerk,” reflects a common and pervasive way of thinking in American culture that runs into tension with good biblical theology.

And what does this common and pervasive way of thinking have to do with Disney princesses, you may ask. Then again, you may not ask that question. But I’m bringing it up in my next post this weekend.