If you are reading this post, somebody probably made you to go to school somewhere along the line.

Most likely, you found yourself in school before it occurred to you that you might have a choice in the matter. All the kids you knew went to school. You did not ask where school came from. You did not hire the teachers, you did not assemble the curriculum, and you did not pass the laws that compelled kids like you to go to school. You just went.

Maybe in third grade you protested and asked your mom or our dad why you had to go to school. Your protests did not matter. School was inevitable.

It has not always been this way. For most of human history, formal education was a privilege for the elites. In fact, there are still places in the world today where children do not have the opportunity or the economic resources to go to school.

In some ways, it is odd that the United States requires all children to attend school. Americans believe in liberty, rights, limited government, the freedom of individuals to make choices, and the chance for people to live their lives the way they want. And yet, parents can be punished for not sending their children to school. Isn’t this a violation liberty, limited

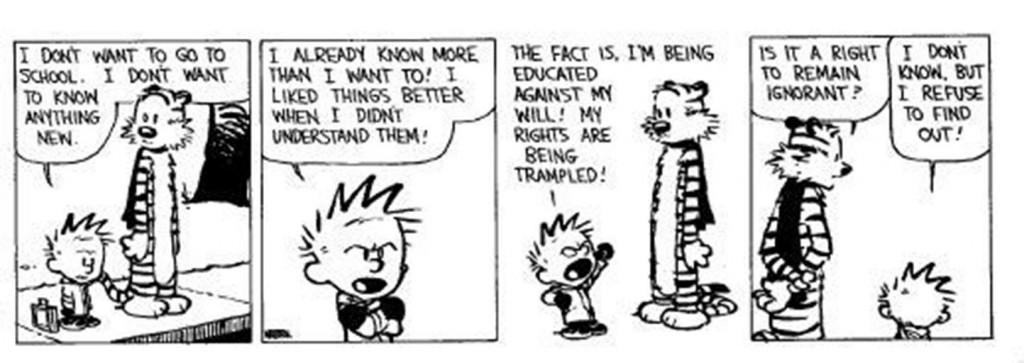

Calvin (of the Hobbes variety) would not have been happy with the Puritans. John Calvin, however, would have approved.

government, freedom of individuals to make choices, rights, and the chance for people to live their lives the way they want? Disgruntled third graders (if they stayed in school long enough to learn about such things) might make this argument. But there it is: in the land of the free, everyone is compelled to go to school.

There are, of course, good reasons for mandatory education. Imagine how different society would be if only a handful of people could read. Imagine how you would be different as a person if you could not read.

You should be thankful, then, for mandatory primary school education. And you should be thankful for those persons in history who built this system.

Disgruntled third graders (if they stayed in school long enough to learn about such things), would be correct to lay much of the blame for this system at the feet of the Puritans. American Puritans, who even required people to engage in leisure activities, had a knack for passing laws that kept individuals from straying from the Puritan way. Believing that a conversion experience was necessary for the elect, the Puritans practiced spiritual disciplines like Bible reading in order to pave the way for conversion and holy living. They also believed that they held a covenant with God that would bring judgment on the whole community if they strayed from the path. By golly, then, Puritan children better learn how to read the Bible. So they passed laws requiring each town to provide a schoolteacher who knew Greek and Hebrew. (I have a Ph.D., but I would not be qualified to teach first grade in colonial Massachusetts). As a result, Puritan New England ended up with some of the highest literacy rates in the world – literacy rates that included females, I should add.

In the early 1830s, the common school movement sought to make education mandatory for children across the United States. Who spearheaded the movement? Yankees from Massachusetts, who were building upon two centuries of educational practice. Their purposes had shifted somewhat from their Puritan ancestors. Horace Mann, who led the charge, believed that mandatory education was necessary for good citizenship, democracy and the health of society. Today, purposes have shifted somewhat again, as Americans tend to think of mandatory education as necessary for a strong economy. We differ on the ends of mandatory education, but a theme of the common good runs through it all.

This is no small development. With the assistance of plenty of non-Yankees, the idea of mandatory education has spread throughout the world. It is hard to imagine how a modern economy could function without widespread education. It is still seen as necessary for democracy. It is difficult to see how reform movements, like abolition, women’s rights, or civil rights, just to name a few, could have gained traction without widespread literacy. In the modern world, Christian ministries could not function without widespread education; churches simply assume that their congregations are literate. Biblical translation has proven to be a critical component of the spread of Christianity beyond North America and Europe.

In fact, so much of what we consider to be good in the historical developments in the world from the past two centuries have been built upon education, that a person of faith would have to say that God must be behind it all in some way.

And so, give thanks that somebody forced you – and others — to go to school.